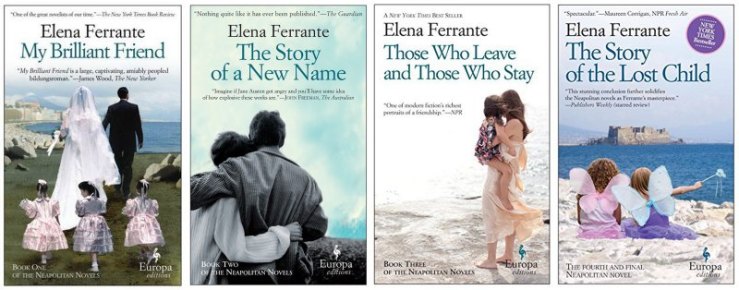

I have been a relative latecomer to Elena Ferrante’s phenomenally successful Naples quartet, starting to read it only around the time the fourth and last instalment, The Story of the Lost Child, was published. What initially intrigued me to pick up the novels was a short article in the New Yorker describing the hype surrounding the publication of the fourth books with bookshops staying open late and putting on special events to allow fans to get their hands on the latest volume as soon as the sales embargo expired at midnight – something usually reserved for Harry Potter or Dan Brown type blockbusters rather than literary novels in translation

I have been a relative latecomer to Elena Ferrante’s phenomenally successful Naples quartet, starting to read it only around the time the fourth and last instalment, The Story of the Lost Child, was published. What initially intrigued me to pick up the novels was a short article in the New Yorker describing the hype surrounding the publication of the fourth books with bookshops staying open late and putting on special events to allow fans to get their hands on the latest volume as soon as the sales embargo expired at midnight – something usually reserved for Harry Potter or Dan Brown type blockbusters rather than literary novels in translation

I opened the first novel of the series, My Brilliant Friend, with apprehension. Would the book be able to live up to the hype, to the almost universal praise heaped upon it? I needn’t have worried. I was hooked virtually straightaway and have since devoured the four volumes in as many weeks with the zeal of the recently converted.

The four novels follow the unlikely friendships of Elena Greco and Lila Cerullo over more than half a century. Both women will take very different paths in life after spending their childhood and adolescence in the poor outskirts of Naples ruled over by minor Mafia thugs. While Elena manages to leave her upbringing behind, goes to university and becomes an author, Lila, the gifted autodidact, is forced to leave school at the age of 16 and stays back in the neighbourhood. Despite their differences, their lives remain entwined as they negotiate the ups and downs, the closeness and the brittleness, the support and the rivalries of their relationship.

The four novels chart early childhood friendships, sexual and political awakenings, marriage, children and the beginnings of old age. In that they are an intricate exploration of class, feminism and politics without ever sliding into becoming a treatise. The novels are juicy, full-bodied tales, bringing to life the smells, sounds and sights of Naples. For works of contemporary literature, the Neapolitan quartet is almost old-fashioned. Like in many 19th century novels there are cliff hangers, big set-piece wedding scenes, holiday romances, political intrigue and even crime. With that Ferrante achieves that rarest of feats, creating a world that is self-contained and anchored in a specific time and locality, while at the same time transcending this world and its characters in a way that resonates well beyond its borders.

The critic James Wood, who introduced Ferrante in the beginning of 2013 to the English-speaking readership with a long review in the New Yorker, quite rightly referred to them as a bildungsroman – a genre popularised in the 18th and 19th centuries describing the hero’s quest for identity through a series of trials and tribulations. Elena and Lila’s story follow this pattern as they seek, in their very different ways and with varying degrees of success, to liberate themselves from their upbringing, from the casual violence of masculine culture and from the moral code surrounding them.

As a story about an education of the heart and mind, they are also a celebration of the power of the written word itself. Books play a central role in the development of the two characters who read voraciously for a myriad of reasons: to find out about the world, to please lovers, to escape their upbringing and above all to find their own voice against the odds of their backgrounds. The novels clearly are about the female experience, but reading them through the prism of gender alone would not do them justice. Of equal importance is their exploration of class and the necessary betrayals and associated feelings of guilt and shame involved in leaving one’s origins behind.

While using the traditional template of the bildungsroman, the quartet is not by any means a pastiche of its form. What sets it apart from being an exercise in traditional, realistic, linear storytelling is their radical subjectivity. We, the readers, experience the world solely through the eyes of Elena. Everything is filtered by her consciousness – a narrative perspective that adds a modernist twist and emotional honesty. It also led to speculation that they are highly autobiographical, particularly as author and narrator share the same Christian name.

It is an assumption which is no doubt also fuelled by Ferrante’s famous reclusiveness. There are no photos, no author bio. Ferrante is a pen-name and the author refuses to appear in public. Yet, in the greater scheme of things whether or to what extent the books are based on Ferrante’s life is irrelevant as the coda of the novels beautifully illustrates. Elena commits a final betrayal of Lila. Against Lila’s expressed wishes she writes up the story of their friendship. After the publication, Lila promptly disappears without a trace. It is the act of writing itself that erases biography and turns it into a fiction that carries a far greater emotional truth.

Reblogged this on thetranslatedworld.

LikeLike